We Have Got to Talk About Usury (Part XV): Rhegius, Hunnius, Gerhard, and the Setting of a Bright Sun

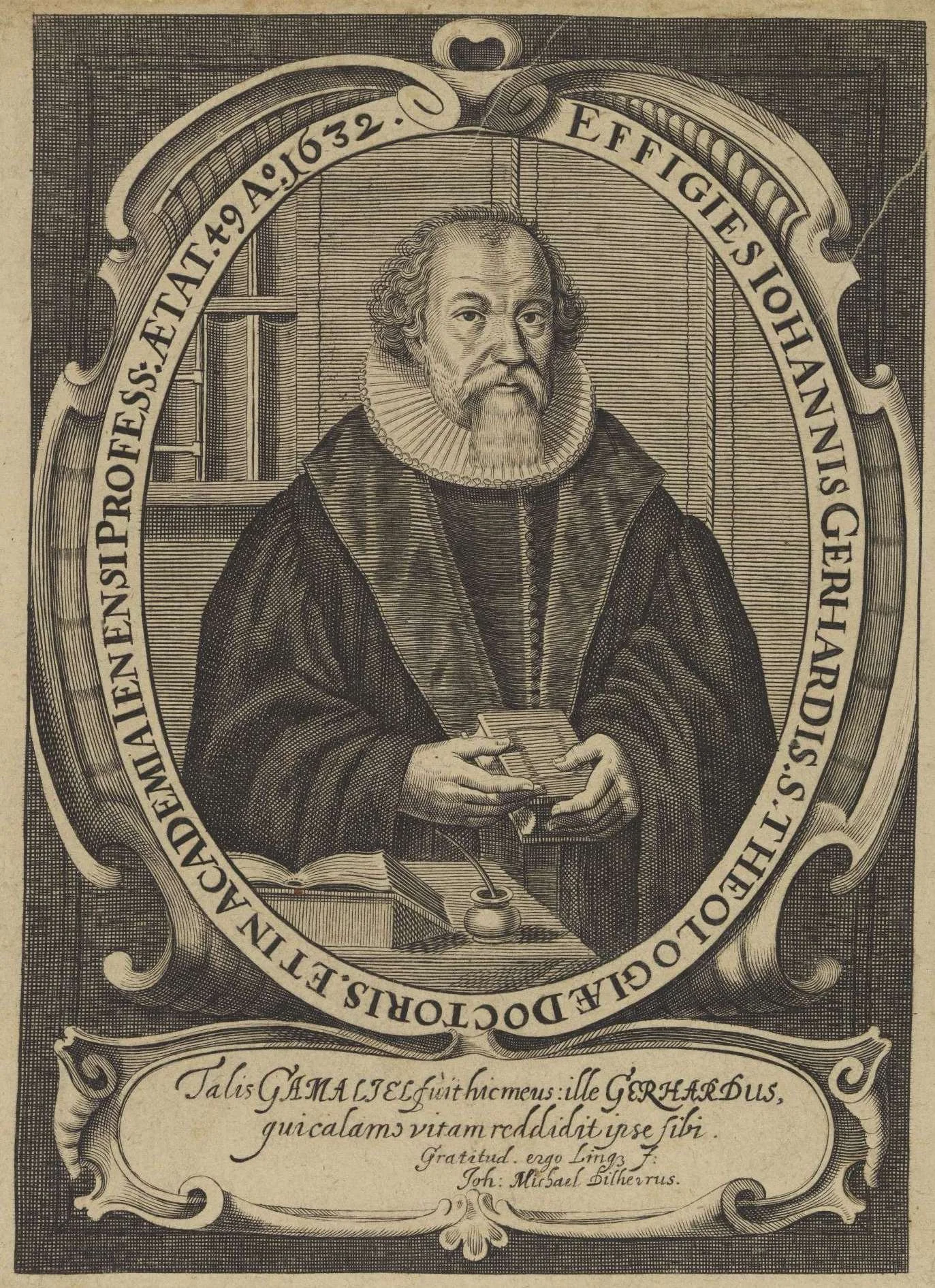

[Johann Gerhard] by Unbekannt (Stecher) - Herzog Anton Ulrich Museum, Germany - CC BY-NC-SA.

The following post is the fifteenth in a series on usury by the Rev. Vincent Shemwell. Rev. Shemwell serves as pastor of Bethlehem Lutheran Church in Johnson City, Tennessee. He graduated from Concordia Theological Seminary in Fort Wayne with the M.Div. in 2022, and received his STM from CTSFW in 2024, writing his thesis on Johann Georg Hamann. The previous installments can be found below:

Part I: Introduction

Part II: The Old Testament

Part III: The New Testament

Part IV: The Church Fathers—Clement of Alexandria through Hilary of Poitiers

Part V: The Church Fathers — The Cappadocians

Part VI: The Church Fathers — Church Councils and Ambrose

Part VII: The Church Fathers—Chrysostom through Leo the Great

Part VIII: Medieval Theologians

Part IX: The Medieval Church Continued—Councils, Canon Law, Dante, and Other Matters

Part X: Luther—His First Foray, in Translation

Part XI: The Strauss Affair and Luther’s Long Sermon

Part XII: Luther on Why Pastors Must Preach against Usury

Part XIII: Miscellaneous Mentions by Luther and a Few Misconceptions

Part XIV: After Luther—Spangenberg, Melanchthon, Brenz, Aepinus, Chemnitz, and Selnecker

“Already in the seventeenth century the bright sun of the biblical teaching against usury had nearly set in the Lutheran Church.” (C.F.W. Walther, Die Wucherfrage: Protokoll der Verhandlungen der deutschen ev. luth. Gemeinde U.A.C. zu St. Louis, Mo., über diese Frage (1869), 37)

“It must be firmly established, on the basis of the clear and unmistakable testimony of Holy Scripture, that usury is not something good in itself or good according to its own kind, nor is it a thing morally neutral, to be judged by its use or abuse, so that moderation would be approved while only excess condemned; rather, it is a practice evil in itself and evil in its very kind, vicious and thoroughly condemned.” (Chemnitz, Loci theologici II (1653), 158–59)

In the sixteenth century, lending at interest for the sake of profit remained prohibited. Limited exceptions were granted for certain contracts construed as sales rather than loans, as well as for interesse, a long-recognized form of indemnification, and antídora, gifts offered at the close of loans as acts of charity on the part of capable borrowers. Yet the pursuit of gain through ordinary interest-bearing loans was rejected by the predominance of the most eminent evangelical theologians, and Luther, throughout his life, continued to urge the excommunication of unrepentant usurers.

By the seventeenth century, however, the landscape had noticeably changed. The distinction between classes of persons in lending, first articulated by Melanchthon and later developed by Brenz and Aepinus, began to be applied to ordinary loans, and it was increasingly claimed that Scripture forbade interest only where genuine harm occurred. Lending was no longer regarded as inherently gratuitous by divine design, nor was interest-taking classified principally as a violation of the first commandment, as had earlier been the case. For a number of seventeenth-century Lutheran divines, the charging of interest was permissible when practiced among the affluent, involving substantial sums borrowed for lengthy periods of time, provided that justice and reciprocity were respected. As Walther noted several centuries later, this perspective dominated for quite a while.

The two figures most responsible for advancing this more permissive (or progressive, depending on one’s perspective) approach were Aegidius Hunnius (1550–1603) and Johann Gerhard (1582–1637). But before turning to their positions, we must briefly return to the first half of the sixteenth century and consider an often-overlooked forerunner of their thought: Urbanus Rhegius (1489–1541).

Rhegius, an early ally of Luther, instrumental in shaping the Augsburg Confession, and hailed by Luther and others as the “Bishop of Lower Saxony,” was arguably the first evangelical theologian openly to depart from the traditional understanding of usury. To fully grasp, for instance, Gerhard’s later insistence on distinguishing between persons in lending, one must first understand Rhegius’ then-unprecedented contention that interest is forbidden only where the borrower suffers injury.

In his 1538 commentary on Psalm 15, Derr XV psalm Davids, Rhegius writes (32–33): “It is now certain and undoubted among all Christians that usury is a great sin, wholly contrary to the love of neighbor. But I think that Gerson, as an experienced man, did not speak in vain when he suggested that one must take care not to label every fixed contract as usurious. For here one must spare the conscience, and not burden it unnecessarily and without the testimony of Scripture. Our true master, Christ, indeed says that one should lend, hoping for nothing in return; from this it is evident that when one lends and takes something over and above the principal, that stands contrary to the teaching of Christ. However, one must also look further in other places of Scripture to see what is necessary to bear in mind regarding this matter. Christ and the apostles teach us everywhere that love of the neighbor is the fulfillment of the second table of the law. For this love is truly the right rule according to which all our doing and refraining toward our neighbor ought to be directed. Whatever is judged and carried out according to this rule is well done. And in this matter, it is quite unnecessary to look to the natural law, for Christ Himself teaches us in Matthew 7: ‘Whatever you want men to do to you, do also to them, for this is the law and the prophets.’ Now if a Christian holds to this rule toward his neighbor in a contract or in a loan, then we ought not immediately judge that contract as usurious.”

As you, dear reader, will see, Rhegius applies this principle not merely to Zinskauf contracts but moreover to ordinary lending. In his judgment, the Old Testament prohibition presupposes that injury is inflicted through the lending practices it proscribes, contrary to the love of neighbor that Scripture requires; therefore, Rhegius contends, where no injury occurs, interest may be allowable (29–33). Part of his rationale rests on the Hebrew terms used in the biblical condemnations of usury (31), which will be treated below. For now, it is enough to observe that Rhegius’ then-uncommon claim that usury is only usury if it harms the borrower, together with the distinction between persons in lending introduced and subsequently advanced by other sixteenth-century Lutherans, furnished Hunnius and Gerhard with a sturdy enough platform to push back against the traditional prohibition against charging interest. Chemnitz was unwavering in his conviction that Scripture plainly condemns interest-taking as evil in itself; but these later men, like Rhegius before them, were less persuaded.

Let us continue with Hunnius. For this pivotal figure and champion of Lutheran orthodoxy, the decisive text for interpreting the usury prohibition does not come from Moses, the psalter, Ezekiel, or Jesus. Instead—strangely enough—he locates it in 2 Corinthians 8:13–14: “For I do not mean that others should be eased and you burdened, but that there be equality.” In explaining this passage in his 1605 Commentarius in posteriorem epistolam D. Pauli Apostoli ad Corinthios, Hunnius reframes Rhegius’ reciprocity-oriented reading of the Old Testament prohibition in light of Paul’s parenthetical admonition to the Corinthian church. He writes (Tomus quartus operum Latinorum (1606), 340): “The reason for the [Old Testament] prohibition is clear, since in this kind of proscribed lending at interest, the loan is given to the neighbor in such a way that, for the lender, there is ease, but for the borrower, there is a great burden, inasmuch as his resources are gradually diminished and eventually exhausted.”

For Hunnius, Paul’s call for equality, where none are eased at the expense of another, sheds light on the rationale behind the Old Testament ban on interest. Accordingly, he interprets that ban not as universal but particular, applying only where the borrower may be harmed. Such cases alone, in his estimation, fall under the biblical condemnation.

On the basis of 2 Corinthians 8:13–14, Hunnius argues that this apostolic principle in lending operates in both directions: lenders must not burden borrowers for their own ease, but borrowers likewise must not impose needless burdens upon lenders. Thus, Paul’s rule of equality, in Hunnius’ judgment, requires not only repayment of the principal whenever possible, but in cases with capable borrowers, also the payment of interest, lest the lender be disadvantaged by the temporary loss of access to his resources without compensation (341).

Hunnius carries this same principle over to Jesus’ command in Luke 6:35, concluding that the command pertains exclusively to lending to the poor (340–41). But when the wealthy are involved—where, in his view, charging interest causes no great burden to the borrower and where Paul’s expectation of equality governs—Jesus’ words simply do not apply. In such circumstances, the lender may rightly expect not only the return of the principal but also the payment of interest, insofar as doing so accords with civil law, which God establishes through magistrates.

In short, Hunnius holds that every biblical passage addressing usury, whether in the Old Testament or in the Gospels, must be interpreted through the lens of 2 Corinthians 8:13–14. Under this approach, his conclusion is straightforward: where no harm is inflicted, there is no usury; and where the borrower can repay with interest, doing so may even be obligatory.

Melanchthon, Brenz, and Aepinus all discerned in Scripture—to varying degrees—a distinction between different classes of persons in lending. Aepinus even called the failure to recognize this distinction “a pernicious error,” something to which even Luther fell victim (In psalmum XV commentarius (1543), 29). Chemnitz, however, firmly rejected this distinction, finding no clear biblical basis upon which the conscience could safely rely. For him, this distinction amounted to nothing more than avarice seeking a pretext (Loci theologici, 162). Hunnius, by contrast, believed he had discovered a way to uphold the distinction and reinforce Rhegius’ interpretation by forcing the entire biblical witness on lending to be read through the narrow aperture of 2 Corinthians 8:13–14. For this reason, he had no difficulty approving Zinskauf contracts entirely severed from agricultural property in which interest rates conformed to civil law, provided that such contracts were made only among those able both to lend and repay with interest.

By Gerhard’s time, the distinction between Zinskauf contracts and ordinary lending had all but collapsed. Already in Luther’s day, many such contracts had been severed from agricultural property and from God’s providential fruitfulness through the land; in practice, they often functioned not as sales but as de facto interest-bearing loans. Luther forcefully condemned these arrangements, though others after him treated them with greater tolerance. To Gerhard’s credit, he recognized that these contracts were effectively loans and refused to perpetuate the fiction that the difference between the two was anything more than semantic. Unfortunately, he nevertheless followed Rhegius and Hunnius, and even advanced beyond them, by conceding that property-less Zinskauf contracts were tantamount to loans while simultaneously arguing that the same rationale used to justify them should be extended to all lending. In this way—perhaps unsurprisingly—the Zinskauf contract proved to be the backdoor through which interest-bearing lending eventually gained legitimacy in the Christian church.

Following Rhegius and Hunnius, Gerhard promoted what soon became the dominant interpretation of the biblical prohibition: namely, that usury exists only where the borrower is harmed, and that Jesus’ command in Luke 6:35 pertains solely to the poor. Yet Gerhard articulated this position with far greater comprehensiveness than either of his predecessors. So let us consider the most determinative elements of his position.

Gerhard addresses the topic at length in his monumental Loci theologici. Since the relevant sections have recently been translated, I will reference that English version. The translation, entitled “On Interest and Usury,” along with the introductory essay “Johann Gerhard and the Good Use of Usury,” appear in the Journal of Markets & Morality 22, no. 2 (Fall 2019): 539–596. Citations below reference both Gerhard’s section numbers and the corresponding journal pages.

From my reading, Gerhard’s primary aim is to defend both the distinction between persons in lending—borrowed from Melanchthon, Brenz, and Aepinus—and the claim that interest constitutes usury only when it harms the borrower, a claim inherited from Rhegius by way of Hunnius. Since the former, for Gerhard, largely depends on the latter, I will address the latter first.

To defend the claim that a distinction between persons must inform and condition the interpretation of Luke 6:35, Gerhard must first make sense of the Old Testament passages that appear to condemn lending at interest in general terms, without qualification. He attempts this by examining the etymology of the Hebrew terms employed (§241; 575). The two most general passages—long cited by the church fathers, Luther, and Chemnitz to forbid all interest-bearing loans—are Psalm 15:5 and Ezekiel 18:8. As Gerhard notes, in Psalm 15:5 the Hebrew term for usury, neshek (נֶשֶׁךְ), derives from the verb nashak (נָשַׁךְ), “to bite.” Thus, he concludes that the interest prohibited here must be understood as “that by which our needy neighbors are bitten, eaten away, and consumed.” This violent imagery, he argues, implies that proscribed interest necessarily involves harm. Evidently, in Gerhard’s view, only the poor can experience such a “bite,” such burden, harm, and oppression. (Space is limited here, but Chemnitz’s discussion of this, from the opposing perspective, is well worth consulting; Loci theologici, 165–66.)

The difficulty for Gerhard’s argument is that Ezekiel 18:8 employs a different Hebrew term, tarbit (תַּרְבִּית), which plainly denotes an “increase” or “multiplication.” Gerhard nonetheless maintains that, given the meaning of this term, “the only thing forbidden is the superabundance by which the needy are drained, weighed down, and burdened,” yet he offers no justification whatsoever for this bold claim from the etymology of tarbit. In truth, “increase” is notably broad, which is no doubt why the church fathers, along with nearly the entirety of Christian tradition up to that point, held that any sum beyond the principal (save interesse and antidora) constitutes proscribed usury. Through the use of tarbit, Scripture reveals that the very act of increasing one’s wealth through interest—amassing superabundance through what is by nature sterile—is itself sinful, irrespective of the borrower’s ability to bear the loss. If anything, the use of tarbit in Ezekiel 18:8 emphasizes that “biting” is not the only harm at issue; the usurer also sins against God through the idolatrous “abomination” of service and devotion to mammon. Take note that of the few sins mentioned, idolatry appears right alongside “taking increase” in vv. 12–13. As Ambrose once put it in his De Tobia (§51–52): “See how the prophet associates the usurer with the idolater, as if to suggest that these transgressions are the same.”

In response to Gerhard’s questionably selective etymological analysis, I simply cite the second Martin (Loci theologici, 162): “Some treat the etymological explanations of certain terms as though they were full and adequate definitions, and in doing so, they fall into error. For example, because in Hebrew the word for usury can signify ‘biting,’ and is therefore said to imply both avarice and injury to one’s neighbor, some argue that the usury condemned in Scripture is not condemned absolutely, as if it were evil in and of itself, but only insofar as it harms one’s neighbor. When interest does not ‘bite,’ however, such as when it is taken from a wealthy man who, by means of borrowed money, can secure some benefit for himself, they claim that it is not a sin and is not condemned in Scripture. These men invent such a distinction: that one kind of usury is ‘biting,’ that is, burdening and oppressing the neighbor, which is prohibited and condemned; but another kind benefits the neighbor, which, they say, is not prohibited but is rather a work of charity…. Yet because this matter must be judged solely by the Word of God, such etymological appeals cannot furnish the conscience with the certainty it requires…. For in the sacred language usury is named not only ‘biting’ but also ‘increase,’ that is, receiving more than was given. Scripture therefore speaks of usury in simple and general terms, without carving out the exceptions or distinctions that these men concoct.”

Ezekiel 18 reads: “‘The soul who sins shall die. But if a man is just … if he has not exacted usury nor taken any increase … he shall surely live!’ Says the Lord God…. ‘But if he has exacted usury or taken increase—shall he then live? He shall not live! If he has done this abomination, he shall surely die; his blood shall be upon him.’” In the same passage just cited, Chemnitz underscores this grave pronouncement and earnestly invites the following questions: In light of such severity, can the conscience rest secure in the belief that usury is only usury when it harms the neighbor? Can one confidently hold that only certain forms of interest-taking fall under divine condemnation, despite the absence of any explicit biblical distinction? And even in the case of neshek, the term most often evokes the bite of a serpent, one that inflicts harm not so much by the bite itself as by the venom that works its destruction subtly and gradually, and is sometimes scarcely noticed at the outset (158). Put otherwise, should anyone stake his justification for lending at interest on something that is, at best, wholly unclear in the Word of God, and even less so in application?

In order to explain away the Old Testament prohibition still further, Gerhard proposes that even if the prohibition is general, it constitutes civil rather than moral law. He writes (§250; 586): “Even if the commands about usury forbid every annual interest payment given for the use of money, [this] is partly moral and partly civil. It is moral in the sense that we should not burden, weigh down, and oppress a neighbor in demanding and taking those interest payments. It is civil in the sense that we not take something from a neighbor in place of interest for borrowed money. The former is general and obligates all people; the latter, however, is special and refers only to the Israelites to whom this had been forbidden because of their proclivity to greed, deceit, and the oppression of their neighbors.”

Yet this distinction between the civil and moral aspects of the usury prohibition cannot explain the fact that “increase” is itself forbidden in the most general, unqualified terms, neither does it account for the context of patently moral law in which the prohibition often appears. Most evidently in Ezekiel 18, but also in Psalm 15, usury is condemned alongside unmistakable moral offenses: idolatry, adultery, unjust violence, etc. Gerhard’s argument proves quite insufficient here. The claim that the general ban belongs only to civil law cannot withstand the witness of these certain texts.

Now Gerhard’s case does not rest solely on Hebrew terminology or Old Testament distinctions. Following Hunnius, he also appeals to 2 Corinthians 8:13–14 to strengthen both the assertion that usury occurs only when one party is burdened for the sake of another’s ease and the related distinction of persons supposedly implied in Luke 6:35 (§235; 564–66). For Gerhard, this Pauline passage establishes that a differentiation among persons must guide lending, and that Paul’s principle operates reciprocally: all parties are to be treated equitably, with no one’s ease secured through another’s burden, so that “the advantages of both contracting parties [are] promoted.”

However, an obvious set of questions arise here: Do not interesse and antidora already fulfill Paul’s requirement? And indeed, the Golden Rule itself? A lender ought not be needlessly burdened or disadvantaged for the borrower’s sake. Interesse has long been recognized as a legitimate indemnity where the lender incurs actual loss and the borrower can afford to rectify the situation. Likewise, with respect to the Golden Rule, on which Rhegius, Hunnius, and Gerhard alike place considerable weight, antidora also satisfy its demands. If a borrower, having benefited from the use of another’s wealth, is able at the conclusion of the loan to respond with a voluntary gift, he ought to do so. These return-gifts, called antidora, have been permitted since at least the medieval period. Even Chemnitz affirms this practice (Loci theologici, 168): “If the borrower, by the use of another’s money, has gained for himself or has escaped some great loss, then surely, by the duty of gratitude and by the mutual regard of charity, he is bound to make a gift in return.”

When Paul urges that there be equality, so that no one is “burdened” while another is “eased,” did he really intend to suggest that Christians should be free to profit from lending, despite the Old Testament witness? Put differently, does “not being burdened” imply a right to secure profit? I readily acknowledge that 2 Corinthians 8:13–14, along with 1 Thessalonians 4:6, are indispensable texts when considering Christian responsibilities in temporal matters. Yet what of Paul’s admonition in 1 Timothy 6? Should we not apply his counsel there broadly as well? Are believers not called to contentment when their basic needs are supplied? And given the biblical ban on interest—a prohibition not easily dismissed—should interesse and antidora be permitted to evolve into interest proper, which is to say, usury? Should these narrow exceptions and voluntary expressions of charity become the structural basis for lending itself, thereby rendering loans something other than gratuitous, contrary to God’s intention (Chemnitz, Loci theologici, 169)? Should Paul’s principle authorize the already-quite-comfortable to obtain yet more ease through profit?

Gerhard contends that what binds by nature may also bind civilly, vested with the authority of political power and backed by external force (§234; 564). So I suppose, believing profit from lending to be in keeping with natural law, he was of the opinion that all this is perfectly Christian. However, his view departs sharply from centuries of the church’s teaching. And how utterly unnecessary such a view is, since, as Chemnitz points out, God has provided other lawful avenues for profit that do not involve men seeking to circumvent a biblical prohibition accepted and perpetuated by the church for millennia. He writes (Loci theologici, 165): “Whoever has money and is able to engage in lawful forms of trade by which he could sustain himself, yet prefers to profit from lending … sins against the doctrine of the sharing of goods, in which God wills that charity be exercised.”

In any event, drawing upon the distinction between persons introduced by Melanchthon and expanded by Brenz and Aepinus, where demanding an amount beyond the principal is forbidden only to those unable to pay it, Gerhard applies this principle beyond Zinskauf contracts to all lending. Combining this with Paul’s rule of equality and the Golden Rule itself, Gerhard formulates his position and puts forward four types of loans. He writes (§253; 589): “The first is the alms loan, when both the principal and interest are forgiven. The second is the free loan … when someone takes back the principal without interest. The third is the compensatory loan … when for money loaned, we demand in addition to the principal amount also some annual payment of interest from our neighbor. The fourth is the usurious loan, which is obviously when we demand illicit and immoderate interest that is forbidden by both divine and human laws, and that weighs down, burdens, and drains our neighbor of his resources.”

The first type of loan is appropriate when lending to the perpetually poor, who deserve alms; the second, when lending to the “indigent,” or temporarily poor, who can at some point repay the principal but no more; the third, when dealing with the wealthy, who can bear the cost of interest; and the fourth, never. Furthermore, even in the third category, the compensatory loan, Gerhard stipulates that interest may never be charged to those who require the loan to meet their essential needs (§239; 571); needs with which Paul, incidentally, exhorts us Christians to be content, by the way. Finally, interest may be taken only when the loan involves large sums for an extended period (§239; 571–72), what he characterizes as “commercial ventures” (§249; 584).

What strikes me in Gerhard’s Loci is how profoundly he, whether inadvertently or by design, misreads Luther on usury. Near the conclusion of his treatment (§256; 594–95), mindful of Luther’s considerable authority, Gerhard wrongly asserts that Luther approved of contracts sanctioned by the magistrates. While Luther did believe civil authorities should reform and regulate the Zinskauf trade, his aim was largely to abolish it altogether, save in cases of extreme necessity (called Notwucher; practiced by widows, orphans, etc.) and where buyer and seller equally shared need and risk in contracts tied to real property with minimal rates. One need only consult Luther’s 1539 To Pastors, That They Should Preach Against Usury to see that he ultimately had no confidence in the magistrates’ handling of usury. Gerhard’s representation of Luther’s view is, therefore, rather reckless and misleading.

It is equally striking that Gerhard invokes the very Golden Rule Luther deployed against interest-taking (Long Sermon; LW 45:292–93). Gerhard seems to miss what Luther grasped with such characteristic clarity: that lending is intended by God to be gratuitous for the sake of our spiritual well-being. Why lend freely? Because Scripture commands and commends such generosity. Luther, together with the fathers, consistently turned to Proverbs 19:17: “He who has pity on the poor lends to the Lord, and He will pay back what he has given.” Even if a lender is materially burdened in this life, he will receive the reward of abundant compensation in the next. Gerhard seems to acknowledge this in his parenthetical reflection on the Parable of the Talents (§248; 583): “Christ does not approve of the practice of usury by which the greedy increase their money and resources; rather, He proposes that we should imitate the profit and increase of money in our spiritual affairs.” One only wishes this insight governed the rest of his reasoning.

For Luther, Luke 6:35 was decisive in his rejection of all interest-bearing loans. For Gerhard, however, this passage was unintelligible unless a distinction between persons were introduced. Otherwise, how does one account for situations in which, ostensibly, the principal ought to be repaid? But for Luther—and for Chemnitz, for that matter—lending must necessarily remain gratuitous. Jesus’ words in Luke 6:35 must be taken at face value. Christians must invariably lend knowing that the loan may, in the end, become a gift, whether by misfortune or by fraud (see Luther’s three degrees of dealing with temporal goods in his “Short Sermon on Usury,” found in WA 6:3–8 and fully translated in Part X of our series). If nothing is returned, God, Who is always eager to become our debtor, will repay handsomely in eternity. If the principal is returned, so much the better. If genuine loss occurs, one may humbly seek relief through an interesse claim, if the recipient is in a position to help. And if both the principal and an additional gift, called an antidoron, are received, these may be accepted with joyful appreciation. But lending must always be shielded from profit-seeking, lest lending cease to be lending (see Luther’s Long Sermon; 291–92). For again, even if we suffer loss now, we gain immeasurably in the life to come.

This brings us to another dimension of Luther’s position, inherited from centuries of Christian tradition, which both Hunnius and Gerhard tend to minimize: namely, that usury violates the first commandment. Throughout his writings on the subject, Luther portrays interest-taking as a form of idolatry, in which the love of money—against which Paul warns so pointedly in 1 Timothy 6—displaces the love of God. In his Long Sermon (LW 45:280–81), he observes that the command to lend freely is “hard and bitter to those who have more taste for temporal goods than eternal goods,” because “they have not enough trust in God to believe that He can or will sustain them in this wretched life.” He then paraphrases Luke 16:10: “He who does not trust God in a little matter will never trust Him in something greater.” In the aforementioned texts, Hunnius and Gerhard never seriously grapple with this concern, though it stood at the heart of the patristic and medieval opposition to usury, and was equally authoritative for Luther. One wonders whether, in their appeal to natural equity, Hunnius and Gerhard were blinded to the peril of neglecting the very first commandment of all.

When this commandment is kept in view, the broader biblical witness clarifies Jesus’ instruction in Luke 6:35. We are called to store up treasure in heaven rather than on earth (Matt. 6:19–21), and we do so through good works, such as gratuitous lending, even when such charity imposes a burden upon us (Proverbs 19:17). Paul’s counsel in 2 Corinthians 8:13–14 in no way contradicts this fundamental truth.

In sum, I do not find the arguments of Hunnius or Gerhard especially compelling, given that the Old Testament expressly condemns “increase” itself and that, as Chemnitz insists, Scripture provides no dependable distinction upon which the conscience may securely rest (Loci theologici, 165–66). Even so, their more permissive (or progressive) approach eventually carried the day, at least for a while.

I think it is entirely reasonable to suspect that this more lenient position triumphed because of political and economic pressure, rather than theological persuasion. Already in Luther’s day, he realized that pastors were suffering persecution for following his admonition and taking a firm stance against usury (see his Appeal for Prayer Against the Turks; LW 43: 221–23; see also To Pastors; LW 61: 322–23, Kindle). And God willing, in the next part of our series, we will back up to the very end of the sixteenth century to investigate a scandalous example of this in the Bavarian city of Regensburg—an episode that may well have deterred the next few generations of pastors from speaking publicly against interest–taking—before proceeding in the following part to the nineteenth century and the early days of the Confessional Revival and the LCMS.

But in closing, I will gladly say this, with all sincerity: Gerhard maintained that interest could only be charged to the wealthy. That is pretty much the position Walther inherited before he returned to Luther’s stricter view around the time of our synod’s founding. Only well into the twentieth century was usury redefined in our circles as merely extortionate interest, without regard for the status of the borrower. But what a more Christian world it would be if we had at least followed Gerhard and continued to condemn all interest charged to the poor and those in temporary distress; if we had at least heeded, on this matter, the most economically “progressive” voice within the Age of Lutheran Orthodoxy. The sun of Gerhard’s teaching would shine brightly enough for me, at least for now. If all we can presently manage is to correct course in the direction of Gerhard’s position, that is, admittedly, a beginning. I would happily and humbly take that W.

Stay tuned.